Every business has loops. Some are driven by fear, some by tradition, some by distraction, some by lack of awareness or industry convention. Loops play out in every aspect of business today. They affect how we think, how we work, how far we venture and how we seek to make change. In the process, they stifle creativity.

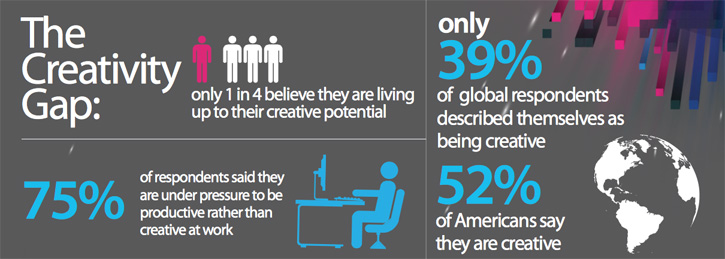

It’s tempting to see creativity as something that only affects those who pursue it for a living, but a 2016 report by Adobe and Forrester Consulting found that 82% of companies see a strong and direct connection between creativity and business results, with companies that think creatively outperforming rivals in revenue growth, market share and competitive leadership.

The link between creativity and innovation

Shawn Hunter makes the excellent point that many companies confuse creativity and innovation. Creativity, he says, is the ability to conceive something original or unusual whereas innovation is about creating or implementing something new that has realised value for others.

“Hunter noted that many leaders focus more emphasis on generating creativity on demand, instead of simply building innovative products, processes and interactions … Once leaders understand the difference between creativity and innovation, they can work on inspiring both among their team members — and building a culture that supports these values.”

Loops cut across that because companies get stuck in doing things in a set way, with no leeway for breaking that framework. It’s easy to say you embrace the new and that you’re looking to break out of how you’ve done things in the past, it’s quite another to act on it. Think of any company that’s gone under recently. Chances are it was killed by a loop – a circular way of thinking and working from which it could not escape. Think of brands that are fighting to stay relevant. What they’re really fighting against oftentimes is their loops, their own logic, as they shed value with every turn. Think of brands that have commoditised. Loops again.

The powerful effects of looping

Loops form easily. Everyone says they’re looking for “competitive difference” – but then, in the race to ‘make it’, they copy each other’s ideas, they mimic each other’s thinking, they catch up with each other’s formulas, they pile onto the latest social fad alongside everyone else. Sometime later they wonder why their sector seems so much more competitive and homogeneous both at the same time. Why wouldn’t it be? As conformity grinds down diversity, there are more and more companies in every sector but less and less real choices for customers.

Loops also close in how organisations react. In extreme cases, they are the business equivalent of a panic attack. They drive businesses to focus on what they think they know to get out of situations they don’t understand or haven’t recognised. They lead to impulsive answers based on the need to do something, anything, but no-one’s quite sure why. Loops hold brands back. When you’re caught in a loop, you can’t move forward.

The irony of loops is that the more people behave in the same way, the more assured they feel and the less distinctive they become.

Loops talk to our love of comfort and habit

People too get used to thinking certain ways, doing certain things. And slowly, inevitably, workplaces get into loops as cultures become set in their ways. They talk themselves into believing that the best way to make their loop more competitive is to leave it as is but to make it go faster – to outpace the other loops. They bind conformity into their language. They do more of the same, more quickly, and congratulate themselves on their productivity.

Same applies to customers. People get used to things, very used to things, and then bored with things. All the way through the first 2/3 of that cycle they want more of the same, and more, and more … And then they want to move on.

It’s human nature to loop because loops are driven by two powerful centrifugal human forces: habit; and comfort.

An innovation crisis

That inclination to do what we know and what feels ‘normal’ has led many firms into what Steve Denning has described as an innovation crisis; one that only makes it harder to think your way out of trouble.

- Only 5% of people working in innovation programs feel highly motivated to innovate, mainly because they say their new ideas are downplayed or dismissed

- Less than a third of firms regularly measure or report on innovation.

- 80% of firms do not have the resources needed to fully pursue any innovations and new ideas that would keep them ahead of their global competitors.

- While 55% say intellectual property is seen as a valuable resource, just 16% regarded its development as a mission-critical function.

We’ve looped ‘innovation’ into how we work to such an extent now that we think we’re doing it as brands and businesses even when we’re not. It has become a process; a way of telling ourselves that a business or brand is moving forward when, in reality, it is not progressing at all, or at least not at the speed that everyone would like to think. (If you’re facing this issue, here’s 9 ways to get others to welcome your ideas.)

How to tell if your organisation is in a loop, and what to do about it

So how do you find and correct something that is so much a part of your day, so much a part of how you think and work, so much a part of what you expect?

First of all, assess your behaviours and those of the immediate and wider teams around you. Here are six sure signs that your business is in a loop:

- You have a “stable” business. (Stability is a dangerous state for any brand, because so often it signals complacency.)

- Sales are arcing down or at least they have plateau-ed but no-one seems worried. It’s explained away as a cyclical blip or as a symptom of the economy.

- “But we have a better product/better people” is used to explain away almost any adverse result.

- There’s a lot of talk about history and tradition. The internal mentality is one of preservation rather than pre-emption.

- Concern about looming or converging competition is dismissed as “scaremongering”.

- The customer pool is shrinking. Everyone’s too busy to notice.

Next, understand that just as people form loops, so it takes people to break loops. And the way to do that is to organise them so that they feel less inclined to repeat the same old patterns. There are some great suggestions in this piece by Dawna Jones on transforming business cultures from complacency to contemporary:

- Shift the collective perspective from linear and analytical to more holistic and one where social, ecological and financial measures have equal weight

- Give people personal responsibility for outcomes

- Trust yourselves as a culture to have challenging conversations and conversations about challenges.

For me, the critical element is one based on thinking by BJ Fogg: that in order to innovate new ideas and ways of working, you must first recognise and acknowledge an agitation: a motive for change that focuses people’s attention. I’ve done too much work in cultures where that motive to break from what feels right is just not there, where organisations are going through the motions of change and innovation, but are not prepared to ask what my wife refers to as “the inconvenient questions”.

More organisations should, in my opinion, spend more time framing their agitation, because, without it, there is no purpose to innovation and performance enhancement.

Then, having broken with the past, and made your people mindful of the need to bring change about themselves rather than waiting for change to come to them, the final step is to look for places to implement meaingful initiatives. So much “innovation” only focuses on creating new things in order to move forward. In reality, as per earlier, it’s often what companies already do, their cultural habits, that make them uncompetitive.

“What have we never questioned?”

Loops form because we are drawn to processes and cycles. We like things that are systematic, that resolve, that are finite. Models give us reassurance that there is structure and sequence. But when ways of doing things become too fixed, they also lock us in.

Feynman saw assumption as the greatest enemy of inquiry

Loop-breaking is about honestly questioning those things that, through force of habit and comfort, have gone un-litigated. My favourite is this: ask “what have we never questioned?” It’s an idea based on the workings of scientist Richard Feynman. His thought: always question what you do know before you enquire about what you don’t know. That’s because Feynman saw assumption as the greatest enemy of inquiry, but instead of limiting his focus to how assumption might jeopardise new fields, he continued to question the levels of in-built assumption in what was accepted as known.

Put Feynman’s question out to everyone who works on making the business better (that should be everyone). And don’t ask once. Pin the question where everyone can see it. Ask every day.

Start small. Start with what feels so familiar, too familiar. “What are we missing here? What’s staring us in the face?”

In many cases, you don’t break through by doing something startling. You disrupt by doing something obvious – so obvious that everyone missed it, because – to Feynman’s point – they didn’t think to question it.

Do you have to stay in a hotel?

What would happen if you caught a car not a taxi?

What should my airline ticket include – and what could we charge if it didn’t?

What would design unthinking look like for example?

A lot of people talk about the fact that creativity is about connecting known things in new ways. Whilst that’s absolutely true, I think there are two other facets of creativity that are often missed. The first is collisions – smashing disparate ideas together is a fantastic way to think about things in new ways. The other of course, in reference to loops, is disconnecting. Because in reverse-engineering why you do the things you do, and why you do them in the sequence in which they are conventionally done, you can discover the assumptions that link one action/idea with another.

Design thinking grew out of a very real need to create rich interactions and develop responsive cultures capable of designing clear and simple answers. Today, its influence is everywhere in how we think and talk about business and brands: experience is now as powerful a consideration as utility; iteration has changed how we organise teams to approach complex issues; and prototyping has shifted the manner in which we test solutions.

But in addition to design thinking, we should probably be simultaneously thinking about concepts like design unthinking. Peeling back what we’ve implemented to question what was tested, and why. Undoing prototypes to look at what we explored and where else that might lead us now. The idea here is not that we stop design thinking (far from it), but that, just like Feynman, we need to continue to question the assumptions of every emerging orthodoxy to ensure that it retains inquirial energy. Because the more that design thinking becomes accepted, the more likely it is that, sooner or later, it will form its own loop, create its own dogma.

There’s an amusing irony in this that I’m both drawn to and worried by: the more that an idea gains traction, the greater the risk that a loop is forming. And therefore the more vigilant that organisations need to be in asking whether such a pattern is helping or hindering competitive momentum.

Finding the right moment to question is probably critical

I don’t yet know when that questioning should take place – I can’t pinpoint a moment – but I am aware that timing is critical. Too soon, and the ideas that have been developed will fail to fire because they are second guessed. Too late, and the value of such deconstruction will be lost. I’m aware too that there’s a certain irony in proposing this. As someone who looks to create solutions every day, there’s huge frustration when ideas aren’t allowed to run their full course or when new thinking comes in to replace or distract from what is working very well.

For me, the question that should be applied to every assumption is this. Are we doing this because it’s right, or are we continuing to do this because investment bias prevents us from calling a halt?

It’s always tempting as a strategist, for example, to develop a theory or model and then to continue to use it because you feel it’s validated. However think about the extent and the speed with which we have come to question many of the assumptions surrounding our world, and it’s easy to see that Feynman’s idea applies to all of us.

Russell Korte wrote a thoughtful piece, From Methodology to Imagination, in which he made a number of interesting observations. We develop theories, he suggests, because we believe them to be an ideal form of knowledge about the world and that the application of such theories increases our capabilities in our world, and because it is impossible to build theory to build theory without a set of ideas, philosophy is vital for theory building. He continues –

“Arguably, more important than a philosophy is the process of philosophizing, which is remarkably similar to the process of theorizing. Philosophizing and theorizing as verbs emphasize the activities of people striving to figure out ways to solve difficult problems and better understand and enhance our world. This activity is an ongoing cycle of doubt and resolution …”

Looping and unlooping

And that surely is Feynman’s point. The power of theories, methodologies, systems lies in developing them, and we shouldn’t be afraid to then un-develop them in order to find new value in them. In other words, the ‘certainties’ in business give us something to work against, a basis for structured dissension, rather than something we always have to work inside. Loops form when we turn verbs into nouns: when, for example, the ability to design think becomes an ‘institution’ called design thinking that mandates what happens and how and doesn’t permit any other way. I’m not saying that has happened – but, as Feynman might say, we should be aware of the risk that it could, and look to review accordingly.

We shouldn’t be afraid to then un-develop what we have come to see as developed

There’s a certain chaos in what I propose – and I make no apologies for that. To me, creativity lives at that nexus of chaos and order, structure and free-form. There’s also an applied refreshment in this idea of taking nothing for granted. In continuing to question what we increasingly agree on, there are opportunities to find new variants, new amendments that enable businesses to build on what is known to work without getting bogged down in only working that way.

It could be argued that loops are an inevitable part of the human condition. I think that’s true, and that perhaps more companies should be looking to capitalise on that. Loops are made to be broken. In fact, I would suggest that’s where their real value might lie.